Derrida for Dummies: a hinge for the rest of us

About a fortnight ago, Joseph Kugelmass wrote a post at The Valve entitled “Derrida’s Obituary, or, Is Literary Theory Too Abstruse?” (to which my answer is “yes”). It subsequently spiralled into a debate about the validity of layman’s introductions or simplifications—Derrida for Dummies, if you will. I’ve said my piece before: I don’t think literary theory does itself any favours as an intellectually respectable discipline so long as it clings to the tangled prose of philosophers instead of extracting the ideas within. Obviously I recognize the necessity of bushwhacking through original texts in serious study, but it’s also high time to admit that many philosophers were terrible writers, and that their ideas can be described in simpler terms without losing too much in the compression. (Derrida is actually quite tame compared to many of his protégés and forebears; once you figure out what he’s trying to do, the Derrida negation test will give you no trouble at all.)

I jumped into the comment-box fray myself, but—in an ample demonstration of exactly what I was saying—others in the discussion phrased the same ideas in more succinct and elegant terms.

But basically I agree that if knowledge is to be knowledge, it has to get past its original writer. If you can only understand the concepts in Derrida by reading Derrida, then you’re not reading him for knowledge, you’re reading him as a literary text.

At their best, [good summaries and guides] provide us with the foundation to read better when we turn to the original text. Even when the roadmap is over-simplified or not quite right, I find that students can question the map more effectively having used it than they could if they only had a first reading to go on.

Ironically, that always seemed to me to be the point of Derrida’s work: to provide a reading—not a reduction but a distillation—of a certain aspect of a philosophical text, so that when we return to the foundational texts—Plato, Rousseau, Hegel, Heidegger, Descartes—we do so with fresh eyes, standing on the shoulder of a giant, so to speak.

It’s odd that Joseph is defending the host/parasite binary in a defense of Derrida.

I also recommend Andrew Seal’s excellent response at Blographia Literaria. Seal makes a crucial distinction that I have been advancing for ages: that a call for more transparent philosophical writing is not populist pandering, but an urgently needed reform for the sake of maintaining a healthy intellectual culture. An excerpt:

Derrida, then, becomes nothing more than a genial literary critic of his own corpus, writing to and for Derrida enthusiasts. This kind of flight into the personal is precisely the move conservative critics take as a sign of the weakness of post-structural thought. Whether or not this is fair, it is highly important to question the value of such a move if it ends up inevitably sticking us with charges of “meaninglessness,” “relativism,” and “charlatanry.” This is the bedrock problem of the mischaracterization of post-structuralism, gender/queer theory, critical race theory, post-colonialism, etc.—the reactionaries listen to us denounce repeatedly the notion of an integrated, coherent, autonomous subject, and then we say something like “well, Derrida didn’t mean for everyone to understand his work—his books are intimate and personal writings for people who take the time to really get to know him.” I’d throw my hands up too, if I weren’t typing.

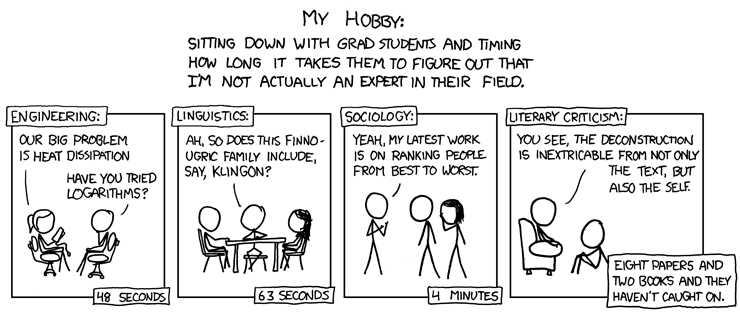

When some defender of theory does make one of these appeals to the “personal,” what they’re really doing is making an appeal to the hieratic: if you’re not an initiate, you shouldn’t be paying attention. If you haven’t taken the time to make Derrida “personal,” you don’t have standing in this field.

Let me be clear: I’m not attacking this move on populist grounds. I’m attacking it on elitist grounds: this is an incoherent and unstable elitism, one more dangerous to the elites than to the masses.